glTF-Tutorials

| Previous: A Minimal glTF File | Table of Contents | Next: Buffers, BufferViews, and Accessors |

Scenes and Nodes

Scenes

There may be multiple scenes stored in one glTF file. The scene property indicated which of these scenes should be the default scene that is displayed when the asset is loaded. Each scene contains an array of nodes, which are the indices of the root nodes of the scene graphs. Again, there may be multiple root nodes, forming different hierarchies, but in many cases, the scene will have a single root node. The most simple possible scene description has already been shown in the previous section, consisting of a single scene with a single node:

"scene": 0,

"scenes" : [

{

"nodes" : [ 0 ]

}

],

"nodes" : [

{

"mesh" : 0

}

],

Nodes forming the scene graph

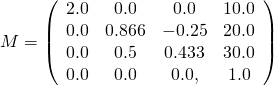

Each node can contain an array called children that contains the indices of its child nodes. So each node is one element of a hierarchy of nodes, and together they define the structure of the scene as a scene graph.

Image 4a: The scene graph representation stored in the glTF JSON.

Each of the nodes that are given in the scene can be traversed, recursively visiting all their children, to process all elements that are attached to the nodes. The simplified pseudocode for this traversal may look like the following:

traverse(node) {

// Process the meshes, cameras, etc., that are

// attached to this node - discussed later

processElements(node);

// Recursively process all children

for each (child in node.children) {

traverse(child);

}

}

In practice, some additional information will be required for the traversal: the processing of some elements that are attached to nodes will require information about which node they are attached to. Additionally, the information about the transforms of the nodes has to be accumulated during the traversal.

Local and global transforms

Each node can have a transform. Such a transform will define a translation, rotation, and/or scale. This transform will be applied to all elements attached to the node itself and to all its child nodes. The hierarchy of nodes thus allows one to structure the translations, rotations, and scalings that are applied to the scene elements.

Local transforms of nodes

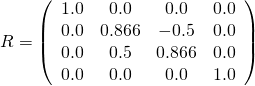

There are different possible representations for the local transform of a node. The transform can be given directly by the matrix property of the node. This is an array of 16 floating point numbers that describe the matrix in column-major order. For example, the following matrix describes a scaling about (2,1,0.5), a rotation about 30 degrees around the x-axis, and a translation about (10,20,30):

"node0": {

"matrix": [

2.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0,

0.0, 0.866, 0.5, 0.0,

0.0, -0.25, 0.433, 0.0,

10.0, 20.0, 30.0, 1.0

]

}

The matrix defined here is as shown in Image 4b.

The transform of a node can also be given using the translation, rotation, and scale properties of a node, which is sometimes abbreviated as TRS:

"node0": {

"translation": [ 10.0, 20.0, 30.0 ],

"rotation": [ 0.259, 0.0, 0.0, 0.966 ],

"scale": [ 2.0, 1.0, 0.5 ]

}

Each of these properties can be used to create a matrix, and the product of these matrices then is the local transform of the node:

- The

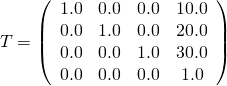

translationjust contains the translation in x-, y-, and z-direction. For example, from a translation of[ 10.0, 20.0, 30.0 ], one can create a translation matrix that contains this translation as its last column, as shown in Image 4c.

Image 4c: A translation matrix.

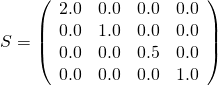

- The

rotationis given as a quaternion. The mathematical background of quaternions is beyond the scope of this tutorial. For now, the most important information is that a quaternion is a compact representation of a rotation about an arbitrary angle and around an arbitrary axis. It is stored as a tuple(x,y,z,w), where thew-component is the cosine of half of the rotation angle. For example, the quaternion[ 0.259, 0.0, 0.0, 0.966 ]describes a rotation about 30 degrees, around the x-axis. So this quaternion can be converted into a rotation matrix, as shown in Image 4d.

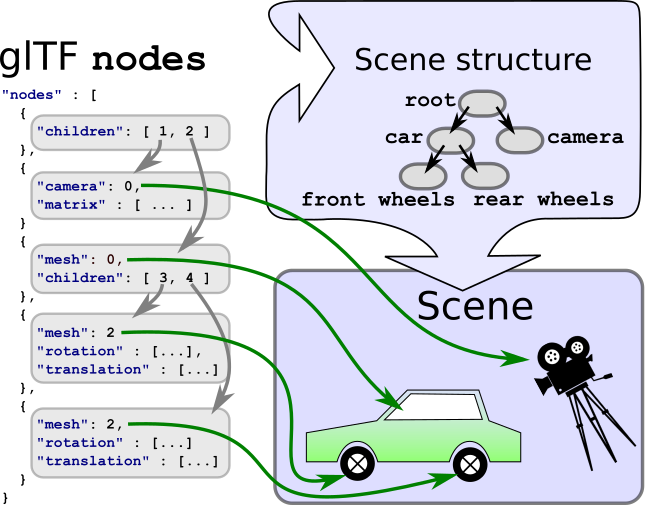

- The

scalecontains the scaling factors along the x-, y-, and z-axes. The corresponding matrix can be created by using these scaling factors as the entries on the diagonal of the matrix. For example, the scale matrix for the scaling factors[ 2.0, 1.0, 0.5 ]is shown in Image 4e.

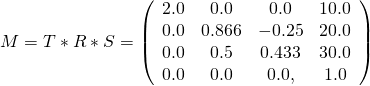

When computing the final, local transform matrix of the node, these matrices are multiplied together. It is important to perform the multiplication of these matrices in the right order. The local transform matrix always has to be computed as M = T * R * S, where T is the matrix for the translation part, R is the matrix for the rotation part, and S is the matrix for the scale part. So the pseudocode for the computation is

translationMatrix = createTranslationMatrix(node.translation);

rotationMatrix = createRotationMatrix(node.rotation);

scaleMatrix = createScaleMatrix(node.scale);

localTransform = translationMatrix * rotationMatrix * scaleMatrix;

For the example matrices given above, the final, local transform matrix of the node will be as shown in Image 4f.

Image 4f: The final local transform matrix computed from the TRS properties.

This matrix will cause the vertices of the meshes to be scaled, then rotated, and then translated according to the scale, rotation, and translation properties that have been given in the node.

When any of the three properties is not given, the identity matrix will be used. Similarly, when a node contains neither a matrix property nor TRS-properties, then its local transform will be the identity matrix.

Global transforms of nodes

Regardless of the representation in the JSON file, the local transform of a node can be stored as a 4×4 matrix. The global transform of a node is given by the product of all local transforms on the path from the root to the respective node:

Structure: local transform global transform

root R R

+- nodeA A R*A

+- nodeB B R*A*B

+- nodeC C R*A*C

It is important to point out that after the file was loaded these global transforms can not be computed only once. Later, it will be shown how animations may modify the local transforms of individual nodes. And these modifications will affect the global transforms of all descendant nodes. Therefore, when the global transform of a node is required, it has to be computed directly from the current local transforms of all nodes. Alternatively, and as a potential performance improvement, an implementation could cache the global transforms, detect changes in the local transforms of ancestor nodes, and update the global transforms only when necessary. The different implementation options for this will depend on the programming language and the requirements for the client application, and thus are beyond the scope of this tutorial.

| Previous: A Minimal glTF File | Table of Contents | Next: Buffers, BufferViews, and Accessors |